Not only do black Americans make up for a considerable share of Country’s audience.They have also contributed – a fact very often overlooked by the media – a great deal to the heritage of Country music as song writers, producers, and singers, who worked against the white cliché of their favourite genre. From afar, it might seem that the Afro-American presence in Country music started and ended with Charly Pride. But whoever takes a closer look at the relationship between black artists and Country music will soon discover a the story of a great love, sorely tried and often denied. In any case, from the very first recording onwards, Afro-American musicians have formed part of the Country tradition. Even before that.“Hillbilly Music“, Bill C. Malone writes in in his standard work „Country Music USA“, „evolved primarily out of the reservoir of folk songs, ballads and dances brought to North America by Anglo-Celtic immigrants absorbing

influences from other musical sources. Of all the southern ethnic groups none has played a more important role in providing songs and styles for the country musician than that forced migrant of Africa, the black.“

The folklorist Norm Cohen even goes so far as to maintain that the worldwide popularity of Country music, compared to other rural American music, can be attributed to nothing but the African ingredient.

Nevertheless, there has always been an exchange between white and black musicians beyond all racial barriers. They often developed the same preferences for certain instruments or lyrics There’s hardly a Soul singer who didn’t make a Rhythm’n’Blues track out of one or the other Country song. Not to forget those black musicians, who have always felt and still feel at home with straight Country music.“Country songs,“ explained English music writer Barney Hoskins, „were very popular among black artists, because they contained elements that Blues-based songs lacked, especially when it came down to the art of story-telling.“

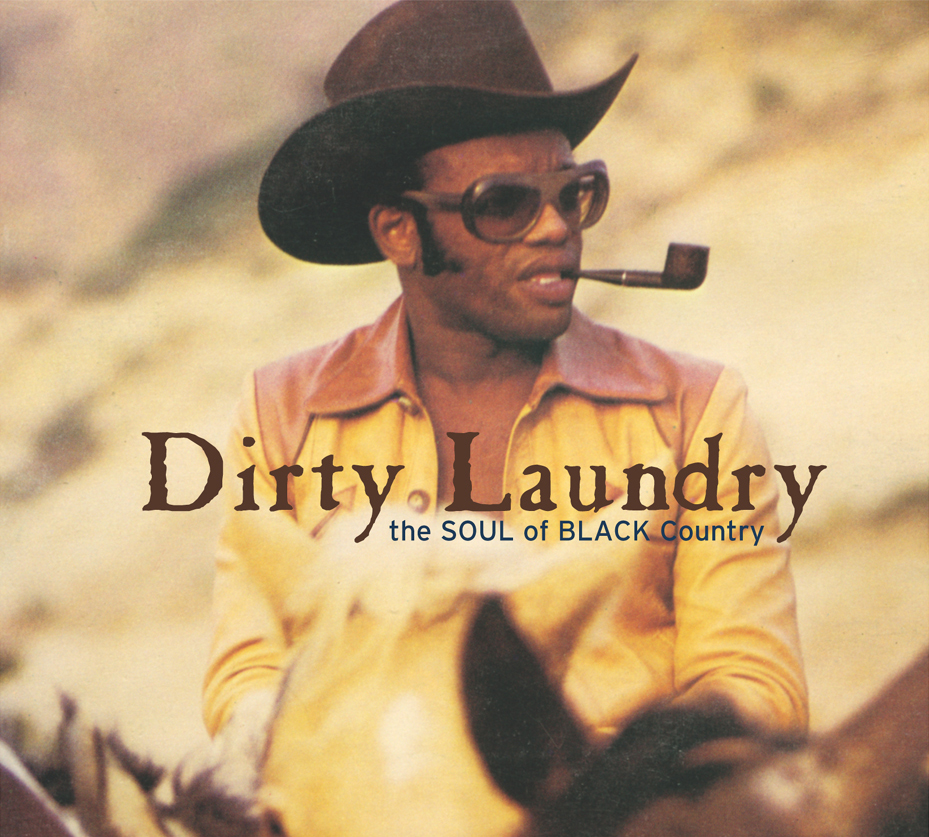

This anthology is a collection of black approaches to Country music. It not only wants to reveal long forgotten treasures of music history, and shed light on the often neglected Country roots of Soul stars, but put Afro-American Country musicians into a context beyond their genre. The main aim is to question implicit truths. Is there something like white and black music? Aren’t Country and Soul music much closer than their categorization by media, video channels and record companies would suggest? And who would maintain that the songs on this album didn’t have Soul?

Jonathan Fischer